How to Drain Your Dragon

Forecasting flashpoints and prospects for "bait & bleed" and bloodletting strategies to counter the CCP's long game.

Unless you have been living under a rock for the last few years, you are aware that tensions between the United States and the People’s Republic of China have been steadily escalating as the PRC has begun to convert its economic gains into increases in military strength. Debates abound regarding whether the two great powers can avoid falling into Thucydides’ Trap wherein an ascending power displaces a hegemonic power causing conflict. Another theory suggests that as Chinese growth begins to slow and the United States begins to awaken to the competition at hand, the CCP will initiate hostilities before it sees some of its advantages evaporate. We’re about six years removed from the publishing of Graham Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap and it is widely accepted that regardless of whether you ascribe to USAF Gen. Mike Minihan’s timeline for hostilities aiming for 2025 (1), or you believe hostilities are more likely to break out in 2027 (2); long term competition between the two great powers, the likes of which has not been seen since the Cold War, is on the horizon.

In a long-term competition between the great powers, the states involved will look for any way they can find to maximize their strength relative to their adversaries on the global stage. In the Cold War this often led to high stakes proxy wars. In this sort of environment, the United States could look to employ what John Mearsheimer refers to as “bait & bleed” or “bloodletting” strategies (3 p. 153) to either lure other powers into wasteful conflicts that drain them of blood and treasure or to make the costs of conflict competitors are already engaged in higher. The purpose of this post is to lay out a framework for identifying opportunities for the United States to engage in these sorts of strategies against the CCP that is based on the weaknesses and sensitivities of the PRC. At a minimum, this will be a useful tool for predicting where flashpoints between the United States and China may occur due to PRC weaknesses and sensitivities. It will provide a roadmap of sorts for future flashpoints between the two great powers by first defining “bait & bleed” and bloodletting strategies in a historical context, then shifting to a discussion of CCP weaknesses and sensitivities that may prompt drive them to military action, and lastly by looking at locations around the world where prospects for mischief and ungentlemanly conduct would be most fruitful in this long game.

Bait & Bleed and Bloodletting Historical Context

In The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John Mearsheimer identifies numerous strategies that states can use to increase their strength relative to rival states in their pursuit of hegemony. Two noteworthy strategies he discusses are “bait & bleed” and bloodletting strategies which both relate to increasing the costs an adversary must pay during a conflict by either baiting them into it or by taking advantage of a conflict they initiate on their own. Between the two strategies, bait & bleed is the more difficult strategy to pull off, because it is dependent on the ability of one state to cause its rival to engage in a protracted war of attrition that they would otherwise not be involved in. Ideally, this strategy would be utilized to get multiple rivals to conflict with each other, and not just be mired in conflict with a lesser state. The intent is ultimately to get rivals into a costly conflict that drains them of resources while the “baiting” state maintains its strength. Historically, there are few definitive examples of a bait & bleed strategy being used. You could argue that Catherine the Great’s efforts to get Austria and Prussia into a war with France following the French Revolution represented a “bait and bleed” strategy, although Austria & Prussia ended up in a conflict with France, Russia’s actions had little influence on it.

The second and more promising strategy of bloodletting differs from “bait & bleed” in that it doesn’t require any baiting. Bloodletting only requires a good attitude, and the will to ensure that conflicts a rival power is involved in become long and costly with the intent to sap their relative strength. Throughout the Cold War, both sides employed this strategy across the globe with the most well-known examples being Soviet Union support for North Vietnam and American support for the Mujahadeen in Afghanistan (3 p. 155). It could be argued that American and European support for Ukraine in its current war with Russia is an example of this strategy as well, although it is worth noting that if the costs of doing so become too great it could be seen as an opportunity for the PRC to achieve a similar effect on the United States.

Methodology for Baiting the People’s Republic of China

Having defined “bait & bleed” and bloodletting strategies in the context of great power competition, this section is going to look at what the likely triggers would be for the CCP to engage in military action around the world. Due to the weaknesses and sensitivities of the PRC, the three most likely triggers to prompt military intervention are 1) the threat of losing access to vital resources abroad, 2) the threat of losing access to the chokepoints that their imports must pass through to reach the PRC, and 3) political instability or threats that play on the CCP’s fear of encirclement by a rival power.

Triggers one and two are very closely related, because they both are ultimately linked to the same insecurity, the PRC’s dependence on imports for the basic needs of its population. While the PRC’s population of 1.4 billion people is one of its strengths, it is also one of its greatest weaknesses. With roughly 20% of the world’s population, the PRC only has 9% of the world’s arable land and just 6% of the world’s freshwater, most of which is contaminated beyond usefulness to humans (4). The massive imbalance between population and resources makes the PRC the world’s largest importer of food and other resources with imports being approximately 14% of China’s GDP. For trigger one, political instability or conflict that places a key source of PRC imports in jeopardy could prompt the PRC to intervene militarily to either keep an ally in power or to secure the locations of resources in the conflict zone.

Disruption to the supply chain of Chinese imports or jeopardization of access to chokepoints are the focus for trigger two. Depending on the year, roughly 70%-80% of PRC imports are brought to China by way of maritime trade. This is one reason why the PRC places such a great emphasis on Belt and Road Initiative projects. The vulnerability that the PRC’s dependence on maritime trade represents has been a key factor in the drive for the PRC to build infrastructure and a naval force capable of securing its supply-chains. For context, approximately 60% of PRC maritime trade and 40% of the PRC’s total trade must flow through the South China Sea (5). All this trade is funneled through a handful of maritime chokepoints including the Malacca Strait, Sunda Strait, and Lombock Strait with the Malacca Strait being the largest chokepoint for trade of the three. For context, the Malacca Strait is less than 3 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, and roughly 80% of PRC oil imports must pass through this chokepoint (6).

Historically, China has been very concerned with encirclement by rival powers. This isn’t a fear that is unique to China, but China’s geography and unique vulnerabilities make it very sensitive to the perception that other countries are attempting to contain or surround China geographically or politically. This high sensitivity stems from centuries of humiliating treaties and treatment at the hands of Britain, France, Germany, and Japan. Resistance to perceived efforts at encirclement has been a key feature of the grand strategy of the CCP since 1949. During the Cold War, fear of encirclement was initially focused on the United States, however in the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split Mao had to grapple with numerous internal issues as well as the prospect of encirclement by the Soviet Union (7 p. 347) as the Soviet Union would become one of the PRC’s biggest rivals in the mid-1960s and 1970s (8 p. 84).

In 1979, PRC justifications for initiating the Sino-Vietnamese War were rooted in concerns related to the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia to remove the PRC-aligned Khmer Rouge (7 p. 347) and fears of Soviet encirclement of China (9). The government of Vietnam was communist, but it was aligned with the Soviet Union and in the late 1970s was beginning to assert itself in the region more which was perceived by Beijing as a threat to the balance of power dynamics they preferred. Although the PRC would invade with at least 200,000 soldiers, the operation would largely be punitive lasting only 29 days to “arrest, and if possible, reverse what he (Deng Xiaoping) saw as the unacceptable momentum of Soviet strategy” in the region (7 p. 371). In this context, the strategy achieved the PRC’s goals despite massive losses to the PRC military.

When forecasting where the likely flashpoints may be in a long-term competition, these are the three most likely triggers that could prompt PRC action. In many ways, you can see the PRC’s acknowledgement of these key vulnerabilities in their efforts to field a maritime force capable of securing and defending its supply chains abroad and breaking out of encirclement in the western Pacific Ocean. With the potential triggers identified, the next step is to look at the map and identify locations that the CCP relies on for resources, chokepoints for PRC imports, and potential areas where instability can be leveraged to prompt a PRC reaction.

Vectors of Mischief

To identify prospects for the three triggers discussed in the last section, you must be able to layer data relating to PRC trade on top of indicators of instability or conflict. When you do this, a handful of regions in the world begin to stick out as obvious danger zones for trade and flashpoints between great powers. You can gain a grasp of this by taking two approaches. The first is to map out PRC imports around the world, focus on a few key products or industries that are vital to the PRC, and then identify areas that have a high likelihood of instability on top of that. Given that the PRC economy is highly diversified and complex, step one is going to be a mountain of data that will be very time consuming to slog through. A more efficient alternative to this is to search for fragile geopolitical environments and then layer PRC economic activity and interests onto those areas.

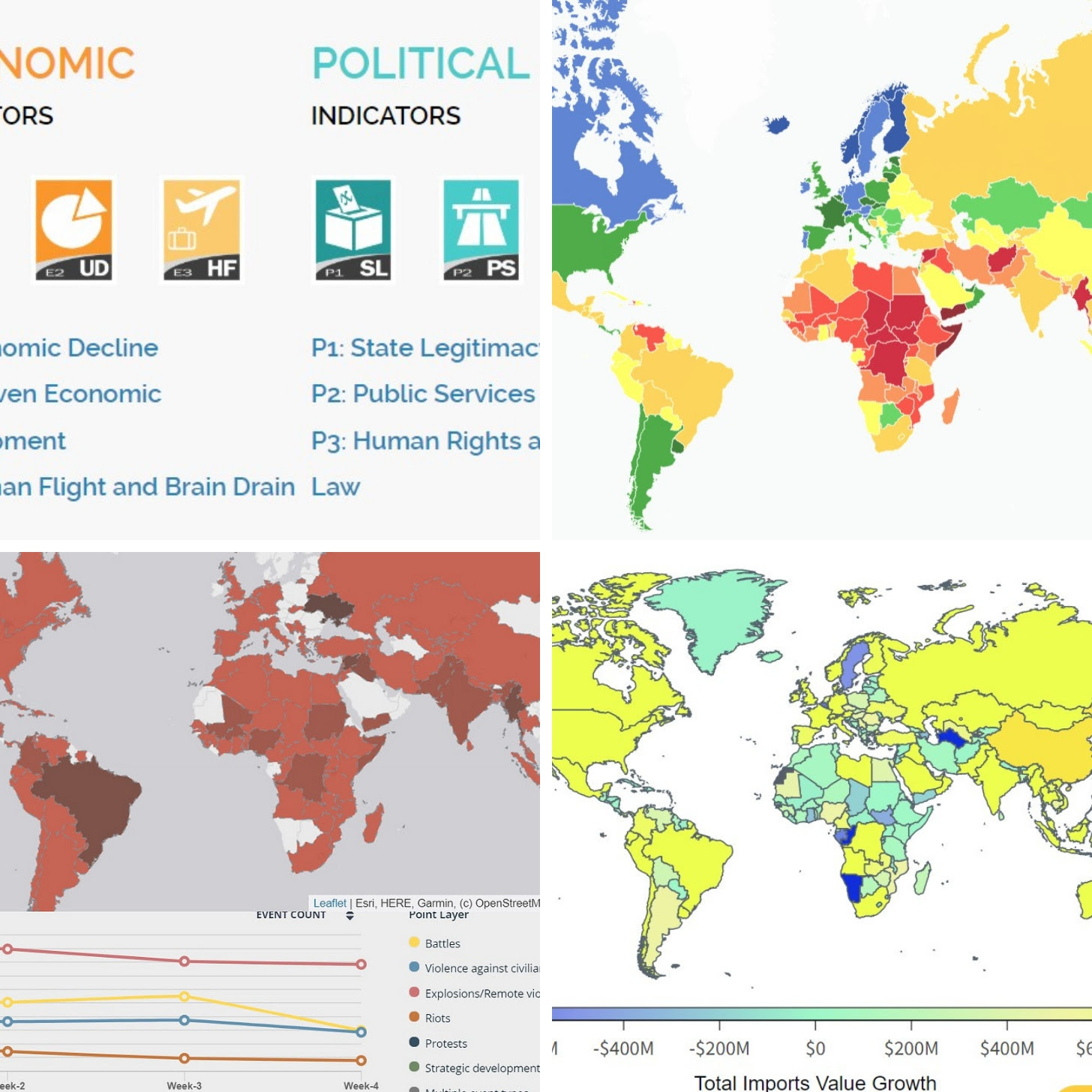

To do this, there are lots of tools that you can use to quickly see where long-term and short-term instability exist. Two that I find particularly useful are the Fragile States Index which is published annually and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) which produces free crisis mapping tools. The Fragile States Index is useful for identifying long-term instability and considers social, economic, political, and cohesion indicators (pictured below for brevity’s sake) with the intent to measure the fragility of states and identify failed states. ACLED on the other hand tracks events related to conflict or political instability on a daily, monthly, or annual basis. The events it tracks and depicts on its map are battles, violence against civilians, explosions reported, riots, protests, and strategic developments. At the macro level, the maps these two sources provide can be very useful. In this circumstance, you can compare the annual fragile states index report and the last month of violence and political strife to see hotspots that have been consistent.

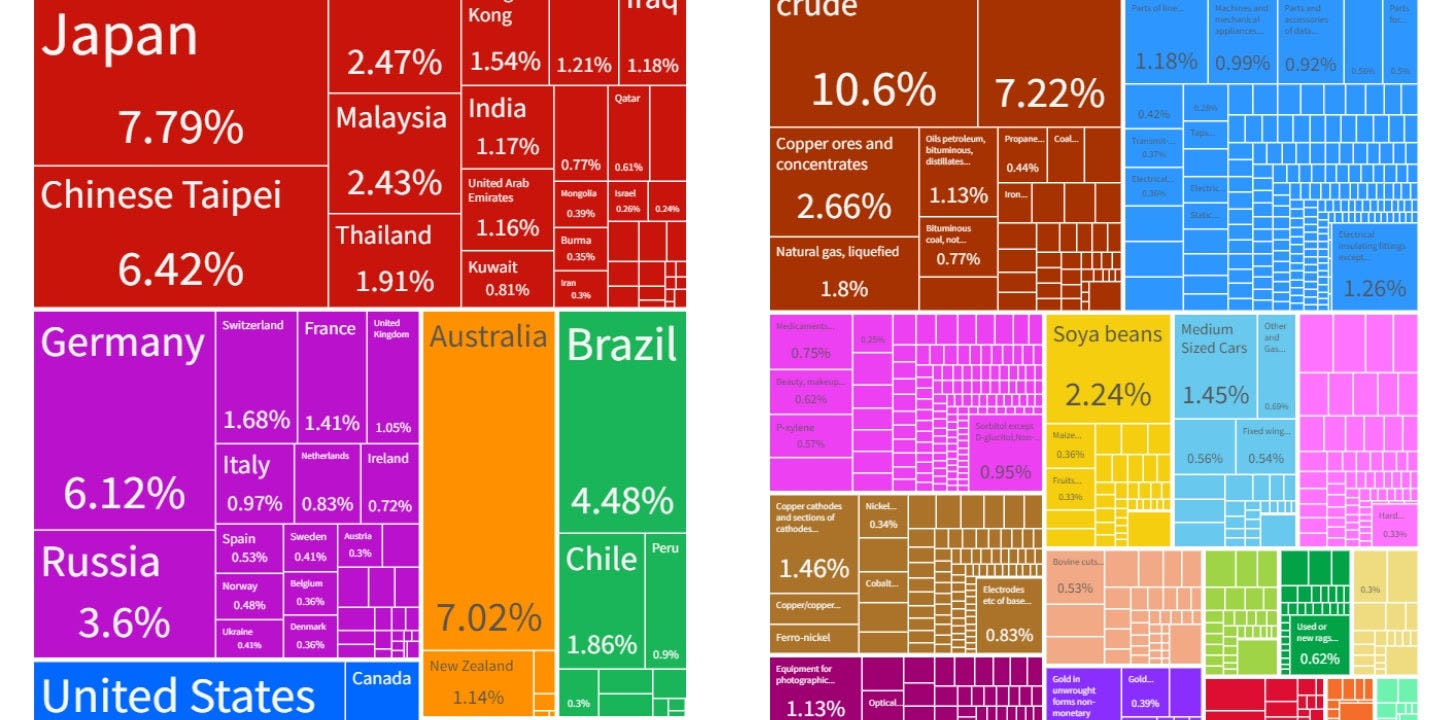

When you contrast those two maps with a map of PRC annual import growth which can be pulled from MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), some overlap and potential for the three triggers outlined in the previous section begin to emerge. The cluster of failed and highly fragile states on the continent of Africa is immediately visible as a risky area for trade, and if group grievance is filtered on its own through the Fragile States Index, Myanmar sticks out as the worst state for this issue in the last year. The next step would be to go state by state and assess the PRC’s dependence on imports from those states, look at the chokepoints those imports must pass through to reach the PRC, and in the case a trigger 3, assess whether the state in question would ping CCP fears of encirclement. At a macro level this is can done quickly using OEC data which can be seen below related to Myanmar, Angola, and Peru which are used as examples.

While Myanmar only represents .35% of total PRC imports, when you dig a little deeper, Myanmar represents roughly 15% of all rice imports into China. That’s not an insignificant amount of trade that is married to the PRC’s fears of encirclement. Angola represents only 1% of total PRC imports, however that 1% contains roughly 10% of all PRC oil imports. This makes Angola vital to PRC interests from a resource dependence standpoint. Lastly, Peru has been the scheme of a great deal of political upheaval and violence in the last 8 months. Peru represents just .9% of PRC imports, but those imports consist of roughly 20% of all PRC copper ore imports.

Layering all this information is very useful in quickly identifying potential vectors for conflict for the PRC as it relates to the three triggers outlined earlier in the post. The key thing is that this is macro level analysis, and further state by state analysis would need to be done at a micro level to identify specific regions, mines, ports, and other infrastructure that would be CCP owned or operated and potentially directly defended by them if they deemed necessary. In future posts, I intend to explore this micro analysis on a state-by-state basis using the methodology in this post to identify countries of interest.

References

1. Kube, Courtney and Gains, Mosheh. Air Force general predicts war with China in 2025, tells officers to prep by firing 'a clip' at a target, and 'aim for the head'. NBC News. [Online] NBC News, January 27, 2023. [Cited: April 30, 2023.] https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/national-security/us-air-force-general-predicts-war-china-2025-memo-rcna67967.

2. Hernandez, Jorge. US predicts date that China will invade Taiwan. [Online] March 6, 2023. [Cited: April 30, 2023.] https://en.as.com/latest_news/us-predicts-date-that-china-will-invade-taiwan-n/.

3. Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York City : W. W. Norton, 2014.

4. Chang, Gordon G. Watch Out: China Cannot Feed Itself. [Online] March 15, 2021. [Cited: December 7, 2022.] https://www.newsweek.com/watch-out-china-cannot-feed-itself-opinion-1575948.

5. CSIS. How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea? Center for Strategic & International Studies. [Online] January 25, 2021. https://chinapower.csis.org/much-trade-transits-south-china-sea/.

6. May, Alexander. The Mitigation of China's Naval Asymmetry via Control of Critical Maritime Chokepoints and the Centerpiece of its String of Pearls in the Indian Ocean. Harvard International Review. [Online] February 10, 2016. https://hir.harvard.edu/mitigation-of-chinas-naval-asymmetry/.

7. Kissinger, Henry. On China. New York City, NY : Penguin Group, 2012.

8. Jian, Chen. Mao's China & The Cold War. United States : University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

9. Garver, John. History of China’s Foreign Relations with John Garver. YouTube. [Online] April 28, 2016.