How to Drain Your Dragon: Angola

A look at PRC related infrastructure and interests in Angola

Disclaimer: If you are reading this via email, please consider viewing on the main page due to the length of the post being too long for email. Much of the information about Angola is below the email cutoff.

A little over a year ago, I tinkered with a process that could be used to identify potential prospects for “bloodletting” or “bait & bleed” strategies against the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The initial post laid out a theory for how these prospects could be identified by cross-referencing major PRC import origins with instability or failed states in the world. The context of this was based on the assertion that whether you ascribe to USAF Gen. Mike Minihan’s timeline for hostilities aiming for 2025, or you believe hostilities are more likely to break out in 2027; long term competition between the two great powers, the likes of which has not been seen since the Cold War, is on the horizon. The initial post can be found here.

This post will be the first in a series that will focus on some of the locations identified through that methodology, starting off with Angola which provides the PRC with roughly 8-10% of its oil imports. Before we get into the details relating to Angola, I am going to review the How to Drain Your Dragon methodology and explain the three primary triggers that could lead the PRC to take action abroad. The final portion of this post will identify and discuss the key infrastructure and locations within Angola that important to the PRC. At a minimum, I intend for this post to be a case study in PRC infrastructure in Angola. So, if that interests you, I hope this is informative. All websites referenced will be linked and all books referenced will be listed at the end.

Review of How to Drain Your Dragon Methodology

To ensure the methodology is understood, this section is going to focus on three foundational aspects of it prior to even glancing at Angola. First is to explain the historical context for “bait & bleed” and “bloodletting” strategies. Second is to identify and explain the three most likely triggers that could prompt PRC military intervention beyond its borders. Third will be an explanation of the analysis done to identify prospective states that the strategy could meet the criteria for a PRC trigger.

Bait & Bleed and Bloodletting Historical Context

In The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John Mearsheimer identifies numerous strategies that states can use to increase their strength relative to rival states in their pursuit of hegemony. Two noteworthy strategies he discusses are “bait & bleed” and bloodletting strategies (1 p. 153) which both relate to increasing the costs an adversary must pay during a conflict by either baiting them into it or by taking advantage of a conflict they initiate on their own. Between the two strategies, bait & bleed is the more difficult strategy to pull off, because it is dependent on the ability of one state to cause its rival to engage in a protracted war of attrition that they would otherwise not be involved in. Ideally, this strategy would be utilized to get multiple rivals to conflict with each other, and not just be mired in conflict with a lesser state. The intent is ultimately to get rivals into a costly conflict that drains them of resources while the “baiting” state maintains its strength. Historically, there are few definitive examples of a bait & bleed strategy being used. You could argue that Catherine the Great’s efforts to get Austria and Prussia into a war with France following the French Revolution represented a “bait and bleed” strategy, although Austria & Prussia ended up in a conflict with France, Russia’s actions had little influence on it.

The second and more promising strategy of bloodletting differs from “bait & bleed” in that it doesn’t require any baiting. Bloodletting only requires a good attitude, and the will to ensure that conflicts a rival power is involved in become long and costly with the intent to sap their relative strength. Throughout the Cold War, both sides employed this strategy across the globe with the most well-known examples being Soviet Union support for North Vietnam and American support for the Mujahadeen in Afghanistan (1 p. 155). It could be argued that American and European support for Ukraine in its current war with Russia is an example of this strategy as well, although it is worth noting that if the costs of doing so become too great it could be seen as an opportunity for the PRC to achieve a similar effect on the United States.

Triggers for Baiting the People’s Republic of China

Having defined “bait & bleed” and bloodletting strategies in the context of great power competition, this section is going to look at what the likely triggers would be for the CCP to engage in military action around the world. Due to the weaknesses and sensitivities of the PRC, the three most likely triggers to prompt military intervention are 1) the threat of losing access to vital resources abroad, 2) the threat of losing access to the chokepoints that their imports must pass through to reach the PRC, and 3) political instability or threats that play on the CCP’s fear of encirclement by a rival power.

Triggers one and two are very closely related, because they both are ultimately linked to the same insecurity, the PRC’s dependence on imports for the basic needs of its population. While the PRC’s population of 1.4 billion people is one of its strengths, it is also one of its greatest weaknesses. With roughly 20% of the world’s population, the PRC only has 9% of the world’s arable land and just 6% of the world’s freshwater, most of which is contaminated beyond usefulness to humans. The massive imbalance between population and resources makes the PRC the world’s largest importer of food and other resources with imports being approximately 14% of China’s GDP. For trigger one, political instability or conflict that places a key source of PRC imports in jeopardy could prompt the PRC to intervene militarily to either keep an ally in power or to secure the locations of resources in the conflict zone.

Disruption to the supply chain of Chinese imports or jeopardization of access to chokepoints are the focus for trigger two. Depending on the year, roughly 70%-80% of PRC imports are brought to China by way of maritime trade. This is one reason why the PRC places such a great emphasis on Belt and Road Initiative projects. The vulnerability that the PRC’s dependence on maritime trade represents has been a key factor in the drive for the PRC to build infrastructure and a naval force capable of securing its supply-chains. For context, approximately 60% of PRC maritime trade and 40% of the PRC’s total trade must flow through the South China Sea. All this trade is funneled through a handful of maritime chokepoints including the Malacca Strait, Sunda Strait, and Lombock Strait with the Malacca Strait being the largest chokepoint for trade of the three. For context, the Malacca Strait is less than 3 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, and roughly 80% of PRC oil imports must pass through this chokepoint.

Historically, China has been very concerned with encirclement by rival powers. This isn’t a fear that is unique to China, but China’s geography and unique vulnerabilities make it very sensitive to the perception that other countries are attempting to contain or surround China geographically or politically. This high sensitivity stems from centuries of humiliating treaties and treatment at the hands of Britain, France, Germany, and Japan. Resistance to perceived efforts at encirclement has been a key feature of the grand strategy of the CCP since 1949. During the Cold War, fear of encirclement was initially focused on the United States, however in the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split Mao had to grapple with numerous internal issues as well as the prospect of encirclement by the Soviet Union (2 p. 347) as the Soviet Union would become one of the PRC’s biggest rivals in the mid-1960s and 1970s (3 p. 84).

In 1979, PRC justifications for initiating the Sino-Vietnamese War were rooted in concerns related to the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia to remove the PRC-aligned Khmer Rouge (2 p. 347) and fears of Soviet encirclement of China (4). The government of Vietnam was communist, but it was aligned with the Soviet Union and in the late 1970s was beginning to assert itself in the region more which was perceived by Beijing as a threat to the balance of power dynamics they preferred. Although the PRC would invade with at least 200,000 soldiers, the operation would largely be punitive lasting only 29 days to “arrest, and if possible, reverse what he (Deng Xiaoping) saw as the unacceptable momentum of Soviet strategy” in the region (2 p. 371). In this context, the strategy achieved the PRC’s goals despite massive losses to the PRC military.

When forecasting where the likely flashpoints may be in a long-term competition, these are the three most likely triggers that could prompt PRC action. In many ways, you can see the PRC’s acknowledgement of these key vulnerabilities in their efforts to field a maritime force capable of securing and defending its supply chains abroad and breaking out of encirclement in the western Pacific Ocean. With the potential triggers identified, the next step is to look at the map and identify locations that the CCP relies on for resources, chokepoints for PRC imports, and potential areas where instability can be leveraged to prompt a PRC reaction.

Process to Identify Prospects

To identify prospects for the three triggers discussed in the last section, you must be able to layer data relating to PRC trade on top of indicators of instability or conflict. When you do this, a handful of regions in the world begin to stick out as obvious danger zones for trade and flashpoints between great powers. You can gain a grasp of this by taking two approaches. The first is to map out PRC imports around the world, focus on a few key products or industries that are vital to the PRC, and then identify areas that have a high likelihood of instability on top of that. Given that the PRC economy is highly diversified and complex, step one is going to be a mountain of data that will be very time consuming to slog through. A more efficient alternative to this is to search for fragile geopolitical environments and then layer PRC economic activity and interests onto those areas.

To do this, there are lots of tools that you can use to quickly see where long-term and short-term instability exist. Two that I find particularly useful are the Fragile States Index which is published annually and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) which produces free crisis mapping tools. The Fragile States Index is useful for identifying long-term instability and considers social, economic, political, and cohesion indicators (pictured below for brevity’s sake) with the intent to measure the fragility of states and identify failed states. ACLED on the other hand tracks events related to conflict or political instability on a daily, monthly, or annual basis. The events it tracks and depicts on its map are battles, violence against civilians, explosions reported, riots, protests, and strategic developments. At the macro level, the maps these two sources provide can be very useful. In this circumstance, you can compare the annual fragile states index report and the last month of violence and political strife to see hotspots that have been consistent.

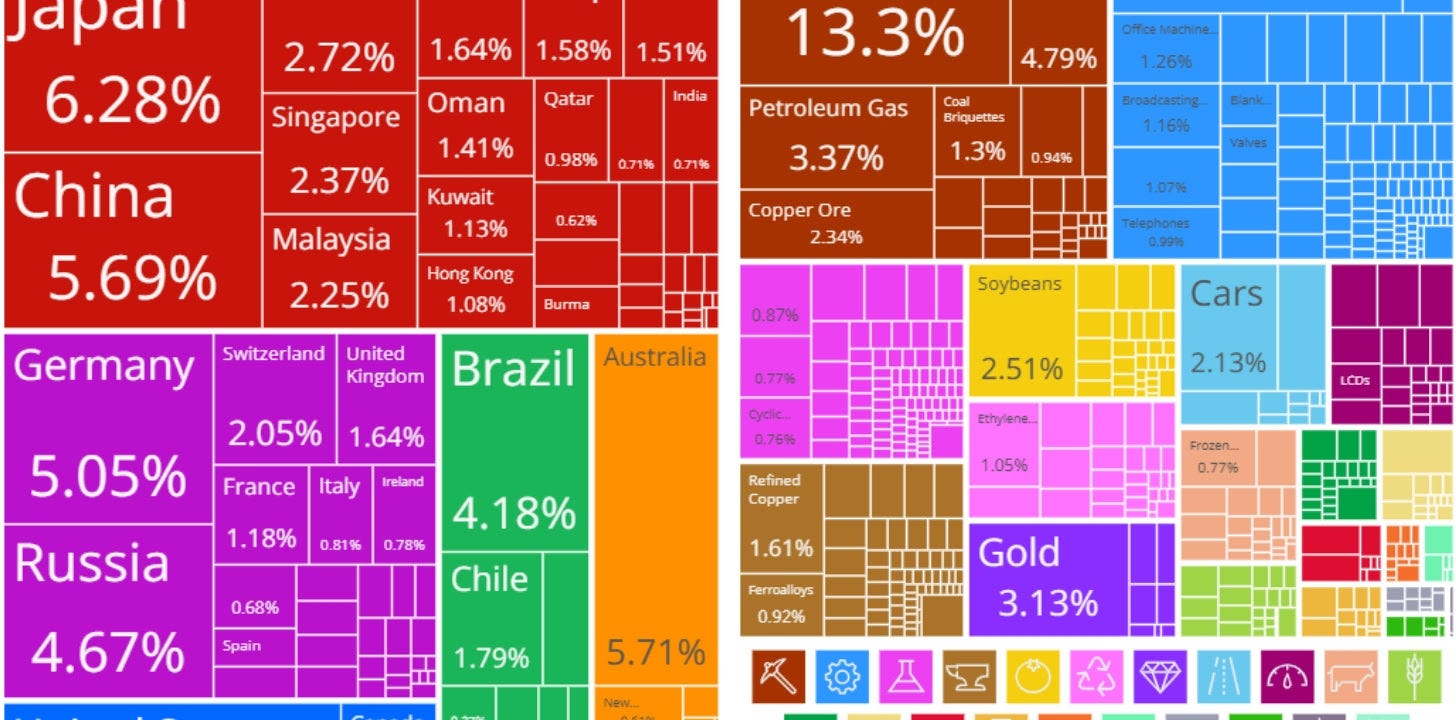

When you contrast those two maps with a map of PRC annual import growth which can be pulled from MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), some overlap and potential for the three triggers outlined in the previous section begin to emerge. The cluster of failed and highly fragile states on the continent of Africa is immediately visible as a risky area for trade, and if group grievance is filtered on its own through the Fragile States Index, Myanmar sticks out as the worst state for this issue in the last year. The next step would be to go state by state and assess the PRC’s dependence on imports from those states, look at the chokepoints those imports must pass through to reach the PRC, and in the case a trigger 3, assess whether the state in question would trigger CCP fears of encirclement. At a macro level this is can done quickly using OEC data which can be seen below related to Myanmar, Angola, and Peru which are used as examples.

While Myanmar only represents .45% of total PRC imports, when you dig a little deeper, Myanmar represents roughly 15% of all rice imports and 2% of petroleum gas imports to China. That’s not an insignificant amount of trade and it is married to the PRC’s fears of encirclement by proximity to China. Angola represents only 1% of total PRC imports, however that 1% contains between 8-10% of all PRC oil imports annually. This makes Angola vital to PRC interests from a resource dependence standpoint. Lastly, Peru has been the scene of a great deal of political upheaval and violence in the last 8 months. Peru represents just .8% of PRC imports, but those imports consist of roughly 20% of all PRC copper ore imports.

Layering all this information is very useful in quickly identifying potential vectors for conflict for the PRC as it relates to the three triggers outlined earlier in the post. The key thing is that this is macro level analysis, and further state by state analysis would need to be done at a micro level to identify specific regions, mines, ports, and other infrastructure that would be CCP owned or operated and potentially directly defended by them if they deemed necessary.

Why Angola?

Considering all of the above factors and criteria, why take a look at Angola? Angola has slowly become a large player in terms of exports bound for the PRC over the past few decades, and integration with the PRC has increased as well through many Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. Specifically, there have been over 300 completed or ongoing projects related to Angolan energy infrastructure by PRC State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) totaling over $10 billion in PRC investments in Angola. Integration and assistance aside, the PRC doesn’t make these investments out of the goodness of their heart and out of compassion for the people of Angola. Angola has lots of resources that the PRC needs, and the PRC relies on Angolan infrastructure for the import of resources the PRC needs from Angola’s neighboring countries.

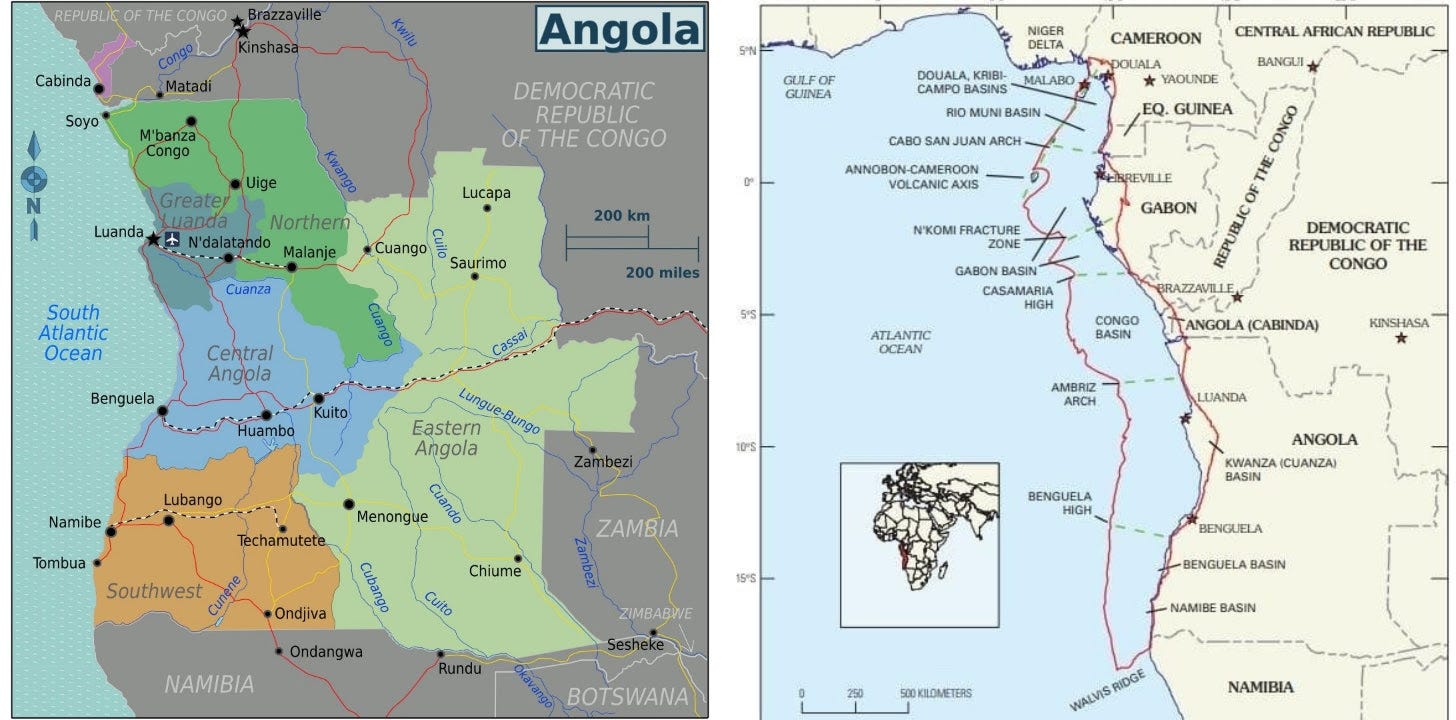

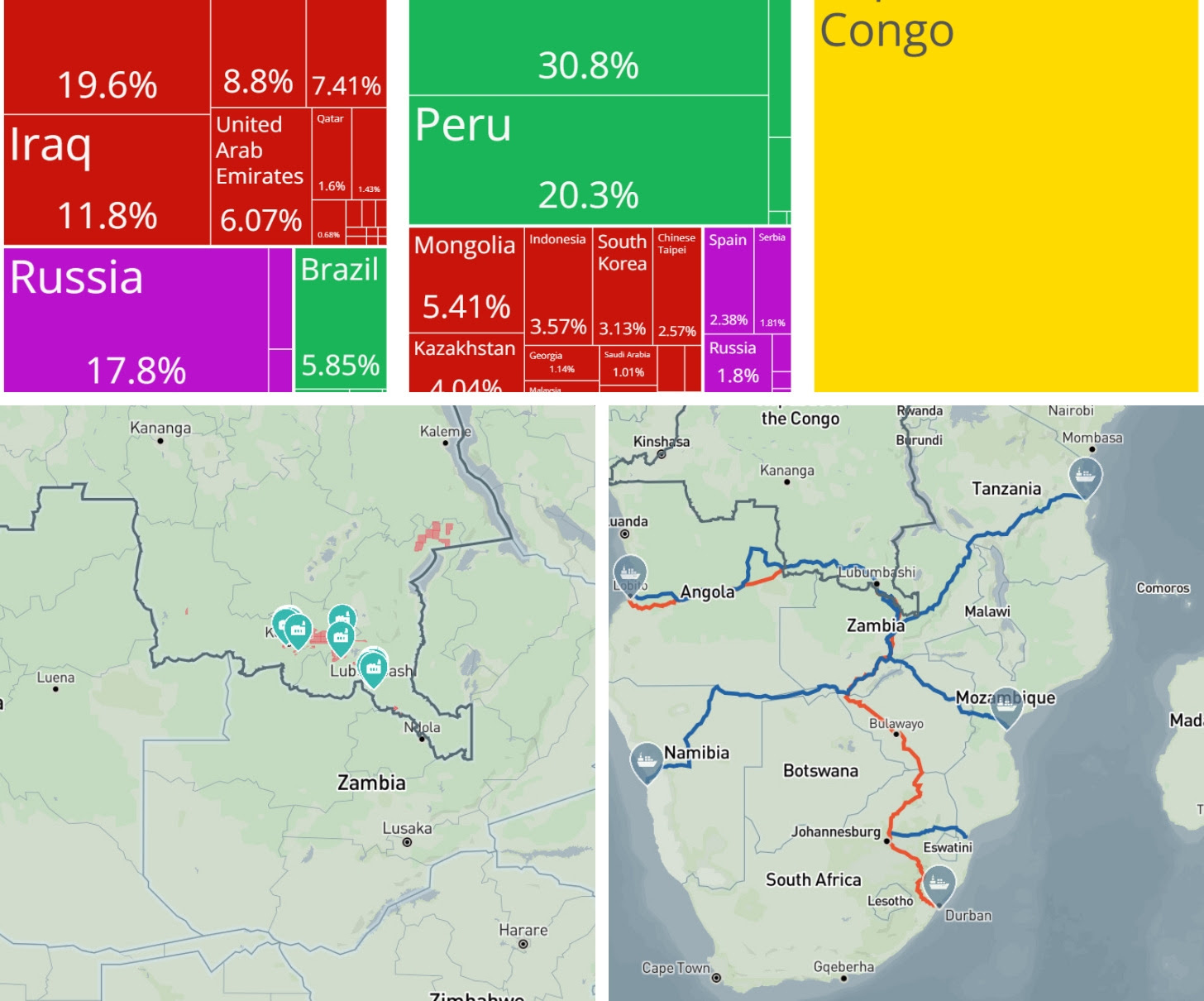

I am going to put these resources into two categories, direct imports from Angola and indirect imports that flow through Angola. As for direct resources that the PRC receives from Angola, the primary resource is oil. As stated above, the PRC imports roughly 8%-10% of all of its crude oil from Angola on an annual basis, with an additional 2%-3% coming from the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Indirectly, the PRC imports a small amount of its overall copper needs from the DRC and 95% of its cobalt from the DRC.

In images 4 and 5 above, you can see the locations for PRC mining and processing projects relates to cobalt and copper within the DRC. Also seen, the trade routes and major ports for the export of these resources with blue indicating highways and red indicating railways. Until recently, the PRC has primarily relied on the corridor which travels south from the DRC to the South African port of Durban but delays due to instability have made routes to ports in Angola and Tanzania more viable.

Important CCP-Related Infrastructure in Angola

In this section, we are going to take a look at the direct imports first. Angola is home to a substantial oil industry with much of its approximately 1.2 million barrels of oil a day in production coming from offshore oil deposits. Among Angola’s oil industry is an extensive investment from PRC SOEs. In particular, PRC SOE Sinopec has had a $1.5 billion stake in Angolan offshore oil and gas for over a decade while PRC SOE CNOOC also has a major stake in offshore oil wells and exploration rights in Angola. Downstream of these stakes is a major PRC interest in the major oil terminals within Angola as well.

In terms of ports and transportation infrastructure within Angola, the PRC has made a significant investment in the Angolan Port of Lobito as well as construction and financing support for the Benguela railway which is critical for connecting inland mining to the Port of Lobito. The investment in the Benguela railway has granted the China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC) significant influence over the operations of this railway. This railway is currently on track (bad pun) to become a major component of an emerging trade corridor known as the Lobito corridor which will make the Port of Lobito a destination for Chinese cobalt and copper minder in the DRC.

In addition to this, PRC SOEs have had heavy involvement in upgrading Angola’s largest seaport known as the Port of Luanda. This port is responsible for roughly 80% of Angola’s non-oil exports. Interestingly enough, the United States and European Union have taken action and promised investment to help develop the Lobito corridor in the future.

Conclusion/Takeaways

Whether we look at these critical chokepoints for trade destined for China as a target in a conflict, vector for mischief in the hopes of drawing China into conflict in the area, or are looking to map out competing economic systems in international trade; it is important to take inventory of these sorts of locations in the world. Locations that have great significance in the grand scheme of things when it comes to great power competition despite existing on the periphery of where most attention is focused. Don’t be surprised to see this region of the world be the focus of American or European efforts to gain economic or diplomatic influence in the near future in order to compete with China over the resources at stake.

References

1. Mearsheimer, John J. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York City : W. W. Norton, 2014.

2. Kissinger, Henry. On China. New York City, NY : Penguin Group, 2012.

3. Jian, Chen. Mao's China & The Cold War. United States : University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

4. Garver, John. History of China’s Foreign Relations with John Garver. YouTube. [Online] April 28, 2016.